Introduction

The nutritional supplement (nutraceuticals) industry is generally burdened by statutory laws that fall into two categories. Notably, those governing medicines and those governing foods. Legislation (statutory laws) is a type of law that is enacted by a legislature or governing body. Regulations, on the other hand, are measures that use rules or restrictions to control human or societal behavior. Regulations can be imposed legally or through self-regulation. As a result, medicine and food production, processing, distribution, retail, packaging, and labeling, in general, are multifaceted industries that are frequently governed by multiple laws, regulations, codes of practice, and guidance in different countries. As a result, this is a complicated subject.

The nutritional supplement industry’s annual retail sales in the United States of America increased from $8.8 billion in 1994 to $18.8 billion in 2003, a 115 percent increase, with a sizable portion of the increase spent on “sports supplements.” The exponential rise in supplement sales can be attributed to manufacturers’ aggressive marketing rather than the development of a more effective nutritional supplement sector. Companies can make unsubstantiated claims about the efficacy of supplements due to the complex legislation governing supplements in most countries. Furthermore, the accuracy of labeling is frequently unquestioned, so any effects of the supplement may be due to contaminants or adulterants in these products that are not reflected on the label. Contamination is defined as deviation from the information on the label. It can happen for a variety of reasons, ranging from accidental to incidental.

The supplement industry is managed in stark contrast to the drug industry, which is governed by strict legislation and controls. Divergence in food and drug laws has created “grey” areas in the “voluntary” declaration of “all” content in a specific nutritional supplement product, making the product manufacturing chain difficult to deal with or even subject to appropriate law enforcement. Even though some consumer protection and anti-doping organizations have requested stricter reporting requirements for supplement manufacturers and harsher penalties for repeat offenders, legislation remains unchanged.

As a result, the goal of this study was to find out how consumers of nutritional supplement products obtain information to help them make purchasing decisions. A self-administered questionnaire was given to people aged 19–40 who were either moderately physically active or competitive. They were questioned about the information on the container label as well as information from sources other than the container label that influenced their purchasing decisions for nutritional supplements. This information was intended to help provide an evidence-based solution to the problem of poorly regulated nutritional supplement labels.

Materials and participants in the study

The University of Cape Town, Faculty of Health Sciences Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC REF 346/2012) approved the self-administered questionnaire. The various institutions or organizations provided written approval, and target and convenient samples/groups were identified and followed up on as part of the recruitment process. The specific locations were the sports halls at the University of Cape Town (UCT), the Cape Peninsula University of Technology (CPUT), and the University of the Western Cape (UWC), as well as the holding camps for the 2012 South Africa Olympic (Pretoria) and Paralympic (Johannesburg) teams before their departure to the 2012 London Olympic Games. The study included all participants who were present at the recruitment sites and provided informed consent.

To ensure appropriate communication, subjects who were physically challenged, visually impaired, or deaf were assisted by the principal investigator or professional support. The questionnaire included seven closed and open-ended questions drawn from a predetermined list of statements. The question statements were simple, and participants could only answer yes or no. Participants could select the respective categories ranging from strongly influenced to no influence from statements with defined options. The physical activity categories were explained to the participants. Organized sport at a high-performance level was defined as competitively physically active. Sport at a social and/or recreational level was defined as moderately physically active.

The questionnaire covered the following topics: general information about participants such as gender, age, and level of physical activity; (ii) had participants purchased nutritional supplements in the previous 12 months; (iii) what information on the container label influenced the purchase of nutritional supplement; and (vi) what influenced the purchase of nutritional supplement if it was not the information on the label. There was no emphasis placed on any of the specific categories listed. The participants were instructed to complete the questionnaire as accurately and completely as possible. The questionnaire took about 2–5 minutes to complete and was given out in various similar classroom settings from July to September 2012.

Results

Participants’ age and level of physical activity

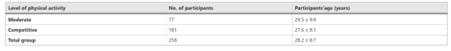

Seventy-seven participants described their physical activity as moderate, while 181 said they are competitively active. Only one participant indicated that he was inactive, so he was excluded from further consideration. Table 1 shows the mean age and standard deviation (SD) for participants whose physical activity was classified as moderate or competitive.

Gender differences in physical activity

There were 159 male participants and 99 female participants in the overall cohort (n = 258). Fifty males reported being moderately active, while 109 reported being competitively active. Females were moderately active in 27 cases and competitively active in 72 cases. Table 2 shows the ages of the male and female groups based on their level of physical activity.

Purchase of dietary supplements

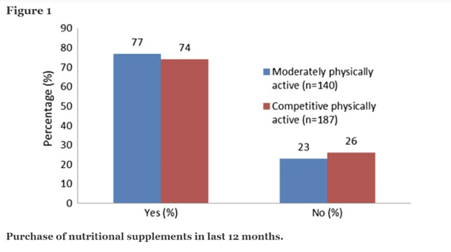

According to the competitively physically active group’s responses, 139 (74 percent) had purchased nutritional supplements in the previous 12 months, while 48 (26 percent) had not purchased nutritional supplements during this period. In the moderately physical active group, 61 (77 percent) reported purchasing nutritional supplements, while 79 (23 percent) reported not purchasing nutritional supplements in the previous 12 months. Figure 1 depicts these data.

Container label information

When the data from the entire group (n = 195) that had purchased nutritional supplement products were analyzed, 132 (68 percent) indicated that information on the container label influenced their purchase, and 63 (32 percent) indicated that their purchase of a nutritional supplement product was not influenced by information on the product label.

When the moderately and competitively physically active groups were compared, the results were similar (i.e., whether the information on the supplement product label influenced their purchase) (Table 3).

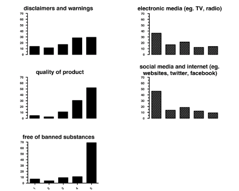

According to the percentage of respondents, the following information on the container label strongly influenced the purchase of nutritional supplements: brand name 36 percent (n = 47), ingredients 40 percent (n = 52), recommended dosage and directions for use 21 percent (n = 28), claims 8 percent (n = 10), disclaimers and warnings 29 percent (n = 36), quality of product 52 percent (n = 67), and free of banned substance(s) 69 percent (n = 89).

Information not found on the container label

The findings are organized as follows (n = number of respondents): (a) coach, gym, and/or fitness trainer, and fellow athletes (n = 67), (b) supplement representatives (n = 63), (c) pharmacist, dietician, nutritionist, and doctors (n = 60), (d) print media (n = 67), (e) electronic media (n = 66), and (f) social media and the internet (n = 65). The five categories were scored in the manner previously described, with scores ranging from absolutely no influence to strongly influenced. According to the percentage of respondents, the following information not on the container label strongly influenced the purchase of nutritional supplements: coach, gym and/or fitness trainer, and fellow athletes 24 percent (n = 16), supplement representatives 2 percent (n = 1), pharmacist, dietician, nutritionist, and doctors 10 percent (n = 6), print media 12 percent (n = 8), electronic media 14 percent (n = 9), and social media and the internet 9 percent.

Discussion

The main finding of this study, which focused on moderately physically active and competitive participants, was that container label information, which stated that the nutritional supplement product was free of banned substances, influenced nearly 70% of the respondents who purchased supplements. The second finding is that slightly more than half of the respondents value the quality of nutritional supplement product information on the container label. The third finding was that when purchasing nutritional supplements, approximately 40% of respondents were strongly influenced by the ingredients on the labels. Other factors influencing the purchase included brand name (36%), disclaimers and warnings (29%), recommended dosage and directions for use (21%), and claims (8%).

These findings are significant because they demonstrate information that is relevant to people who buy nutritional supplements and base their purchase decision(s) on container label information. The lack of specific information regarding “free of banned substances” is a significant determinant in the purchase of nutritional supplement products. Furthermore, there are numerous interactions between drugs and nutrition. In many cases, drugs and nutrients absorb at similar sites and are metabolized and excreted via the same organs. Failure to include this information on the label may have serious consequences for the health and wellness of the supplement’s consumer, especially if the supplement contains a prohibited substance due to contamination or an incorrectly labeled product. The complication of the issue in sports is that, in addition to potential health and drug-interaction consequences, contaminated or incorrectly labeled products may result in inadvertent doping. This data indicates the level and degree of concern that nutritional supplement consumers would have if not all product content was declared on the container label.

Furthermore, concealing information about an adulterated or contaminated nutritional supplement product would influence a consumer’s decision to purchase a product. These findings highlight the importance of conducting regular and batch-to-batch independent laboratory screen testing of all nutritional supplement products for contaminants and/or adulterants.

Repercussions of findings – container label information

Trademark

Based on the study cohort, the trend shows a steady increase in the number of respondents who were not influenced by the brand name (13%) to those who were strongly influenced (36%) by the brand name. Marketers could use this discovery to encourage consumer brand loyalty.

Ingredients

Seven percent of respondents were not influenced by ingredient content, while 40% were strongly influenced by ingredient content. The significance of ingredients in this study is supported by research in Cohen and Lachenmeier’s publications. Their findings raise concerns about some manufacturers’ evasive behavior, which makes laboratory detection of undeclared ingredients difficult by incorporating pharmaceutical analogs into their products. The fact that these analogs have never been studied in humans adds to the situation’s complication. Misleading advertising can also harm consumers’ health if non-approved ingredients are used or contamination occurs.

Dosage recommendations and usage instructions

According to the study cohort, there was a similarity in the number of respondents who were uncertain (25%), moderately (27%), and strongly influenced (21%) regarding recommended dosage and directions for use. This observation raises concerns and demonstrates that respondents may not have a clear understanding of the significance and potential consequences of this type of information if not applied correctly.

Claims

The findings of this study are concerning because a higher percentage of respondents (30%) were unsure whether claims information influenced their decision-making. The findings of this study are supported by the work of Lachenmeier and Petroczi, who claim that advertisements with claims, typically health or disease claims, are misleading or scientifically unproven, despite regulations prohibiting such statements. Furthermore, because of market characteristics, enforcement is more difficult than it is for food or feed, but the consequences may be more severe because supplements are concentrated.

Disclaimers and cautions

Based on the study cohort, the number of respondents who were moderately (30%) and strongly (29%) influenced by disclaimer and warning information in making purchasing decisions was similar.

Product quality

The trend in product quality was similar to the trend in brand name and ingredient information, indicating an exponential increase in the number of respondents who were not influenced (5%) to those who were strongly influenced (85%). (52 percent). This finding is supported by Cohen’s research, which shows an emerging risk to public health due to potential supplement overuse and a lack of enforcement. Petroczi goes on to describe supplements that were found to contain more or less of the substance listed on the label, as well as contamination as a result of poor-quality control measures during the product manufacturing stage.

Free of prohibited substances (s)

When it came to purchasing supplements, the number of respondents who were not influenced (7 percent) by the supplement being free of banned substances was lower than those who were strongly influenced (69 percent). The study cohort studied emphasizes the importance and assurance of a product being “free of banned substance(s).” What is concerning in the context of this finding is that a recent paper demonstrated that for consumers to make informed decisions, there was a need to alert those consuming nutritional supplements of the possibility of banned substances being present in products. Only 5% of the product labels examined in that study included information on “the presence of banned substances in the supplements.” A supporting paper that evaluated the regulations, legislation, and claims associated with nutritional supplement products concluded that consumer protection provisions should encourage higher levels of policy development, regulatory enforcement, and consumer education. Petroczi also reports on the discovery of dangerous substances in many supplements, such as illegal anabolic steroids with serious known side effects. This is a cause for concern, and it emphasizes the importance of being aware of the health risks associated with certain hormonal substances and stimulants. This awareness may lead people to seek out “natural” supplements that claim to be free of such ingredients.